History of the Pinkas Synagogue

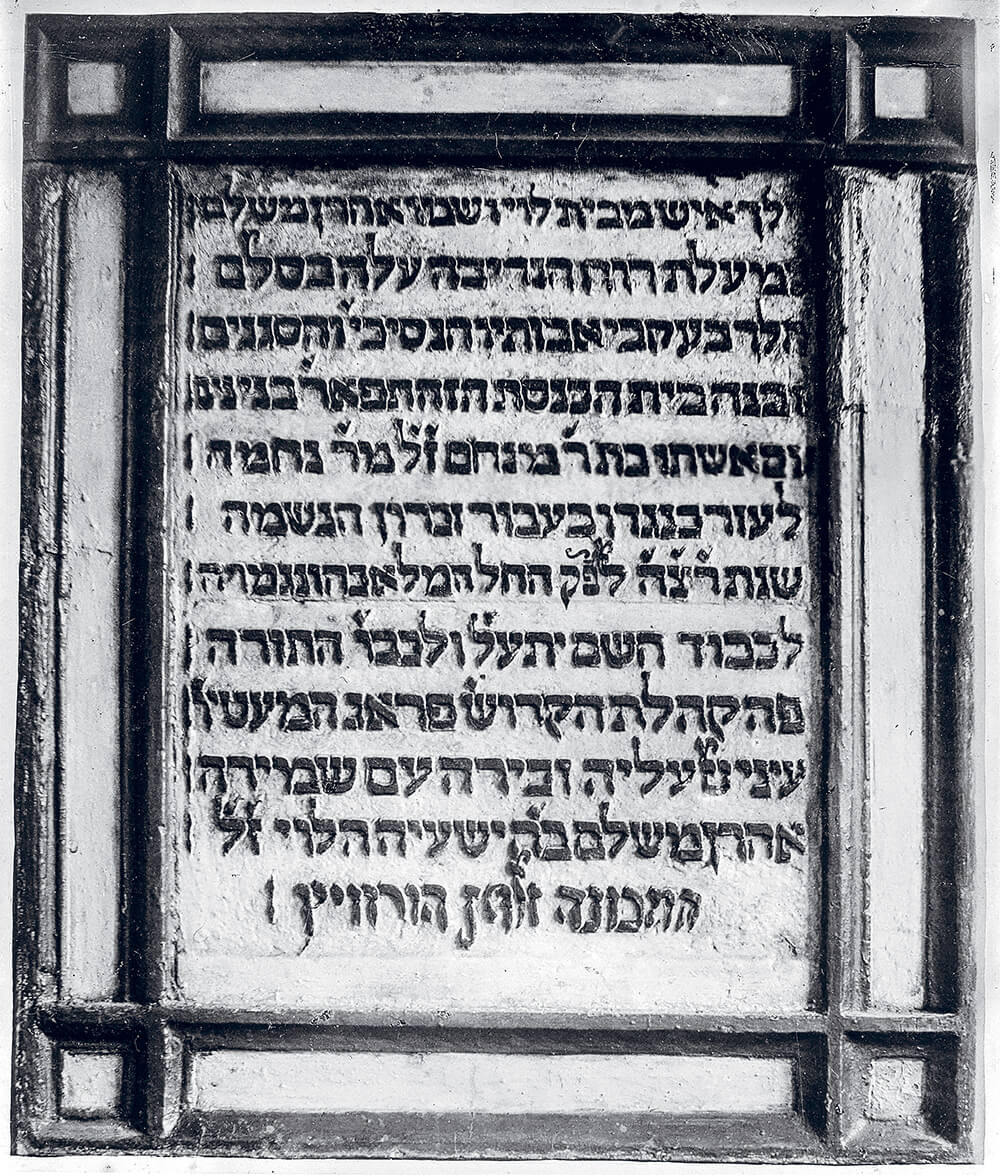

After the Old-New Synagogue, the Pinkas Synagogue is the oldest and architecturally most valuable monument in Prague’s Jewish Town. Before 1492, there was a small prayer hall on this site (in the Coats of Arms House), which was situated at the west end of Široká/Židovská Street. The property was rebuilt after 1519, when Aaron Meshulam Horowitz – one of the Prague Jewish community’s most influential figures – became the sexton of the synagogue. According to the commemorative plaque in the vestibule, the construction of the Synagogue was completed in 1535. The synagogue is allegedly named for Israel Pinkas, the original owner of the Coats of Arms House.

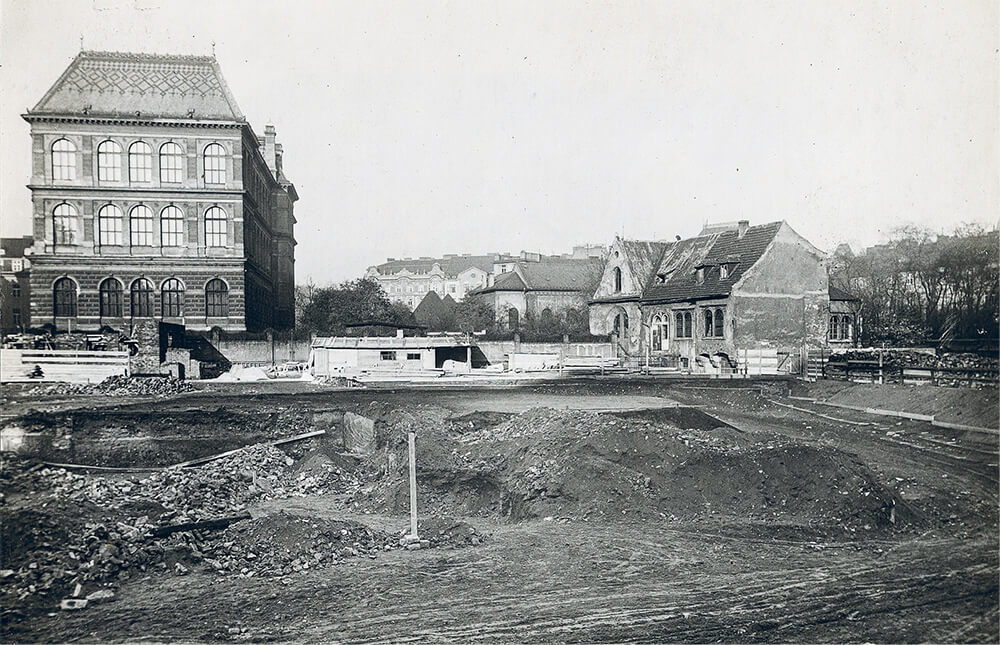

Pinkas Synagogue during the redevelopment of the Jewish Town. Jan Kříženecký, 1909.

Prague City Archives, Photograph Collection, Call No. XI 996Text of the commemorative plaque in the Pinkas Synagogue: “And a man arose in the house of Levi and his name was Aaron Meshulam and he mounted the ladder of his bountiful spirit – he walked in the steps of his fathers, princes and leaders, and he built this synagogue, the splendour of buildings, with his wife, daughter of Rabbi Menahem of blessed memory, Neham, who is to him a helpmate and a memory of soul. In the year 295 according to the minor era (i.e., 1535) the work was begun and was completed to the honour of God most high and to the honour of the Torah, here in the holy community of Prague, crowned – the eyes of God are upon it – for memory and protection. Aaron Meshulam, son of Rabbi Isaiah Levi of blessed memory, known as Zalman Horowitz.”

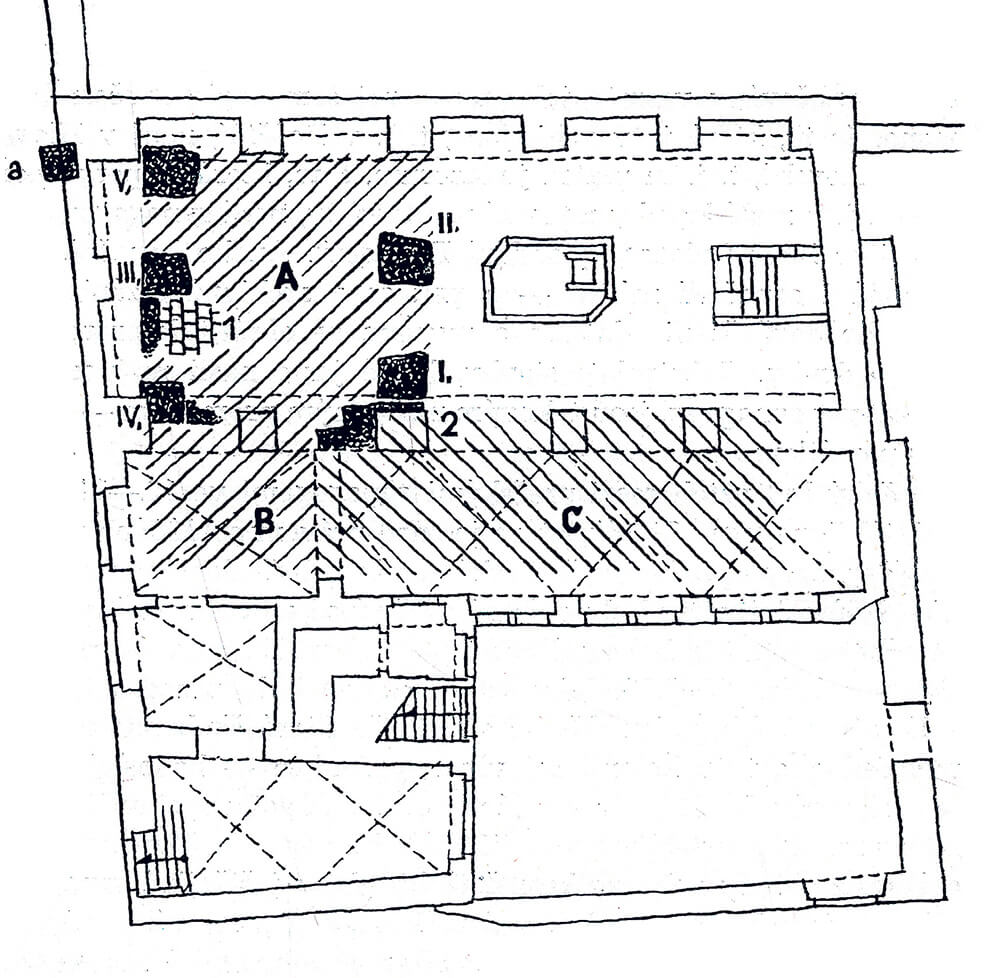

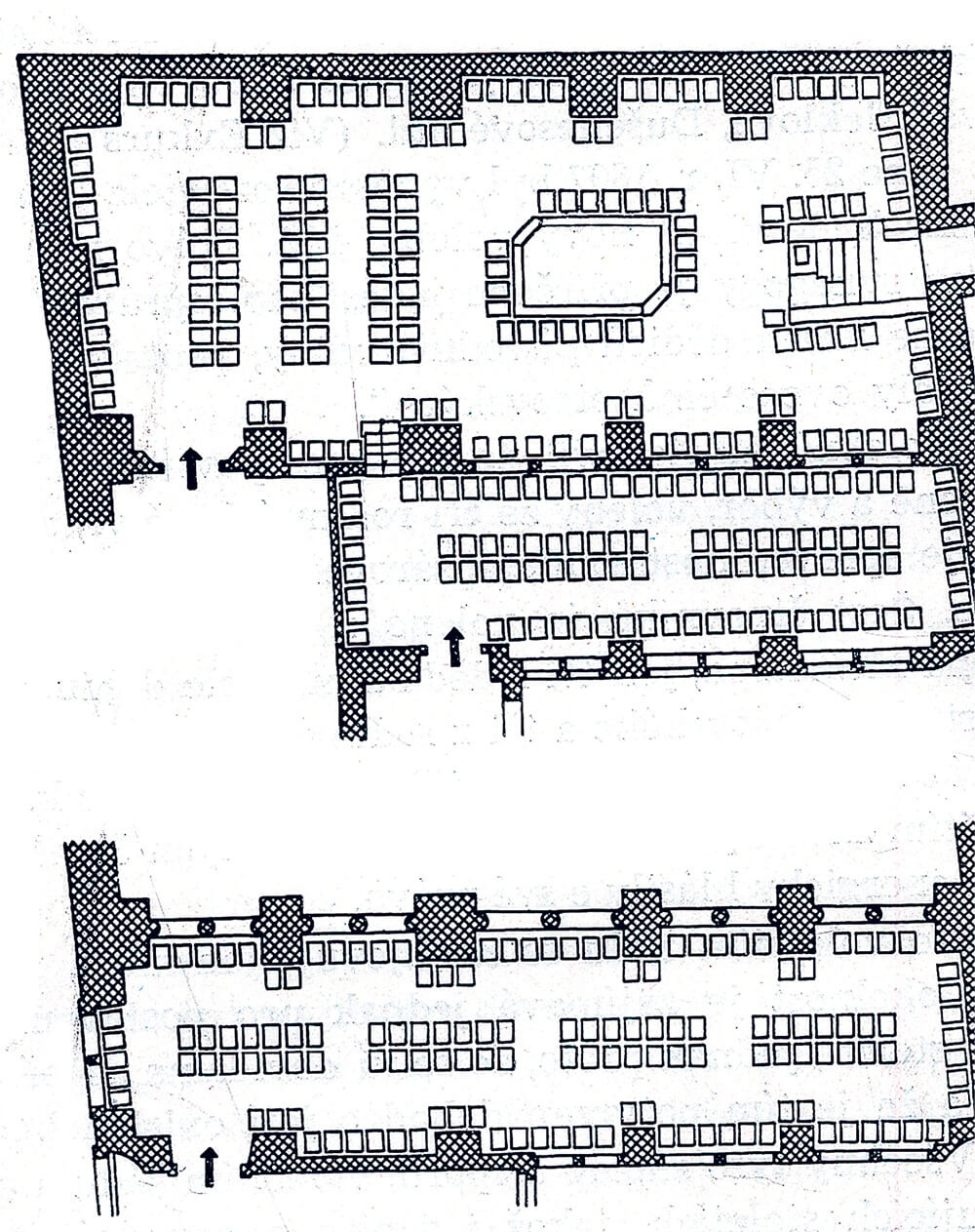

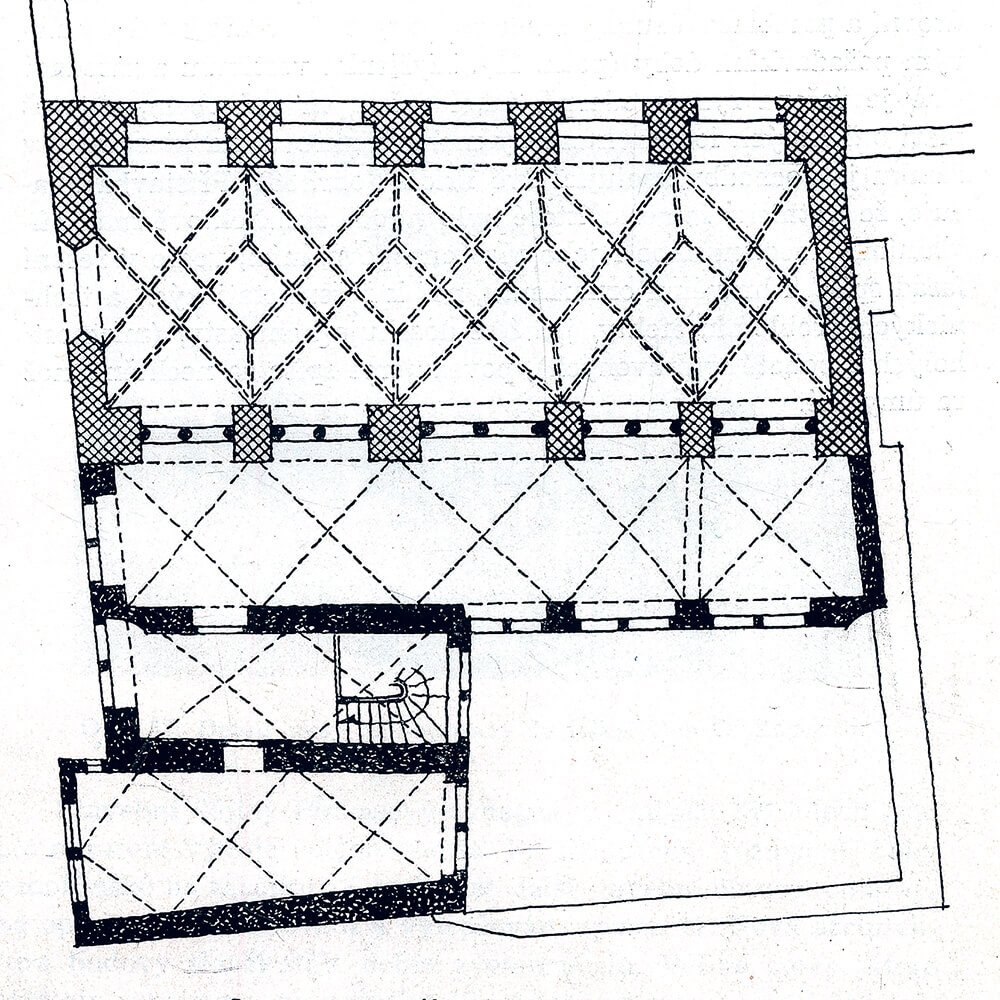

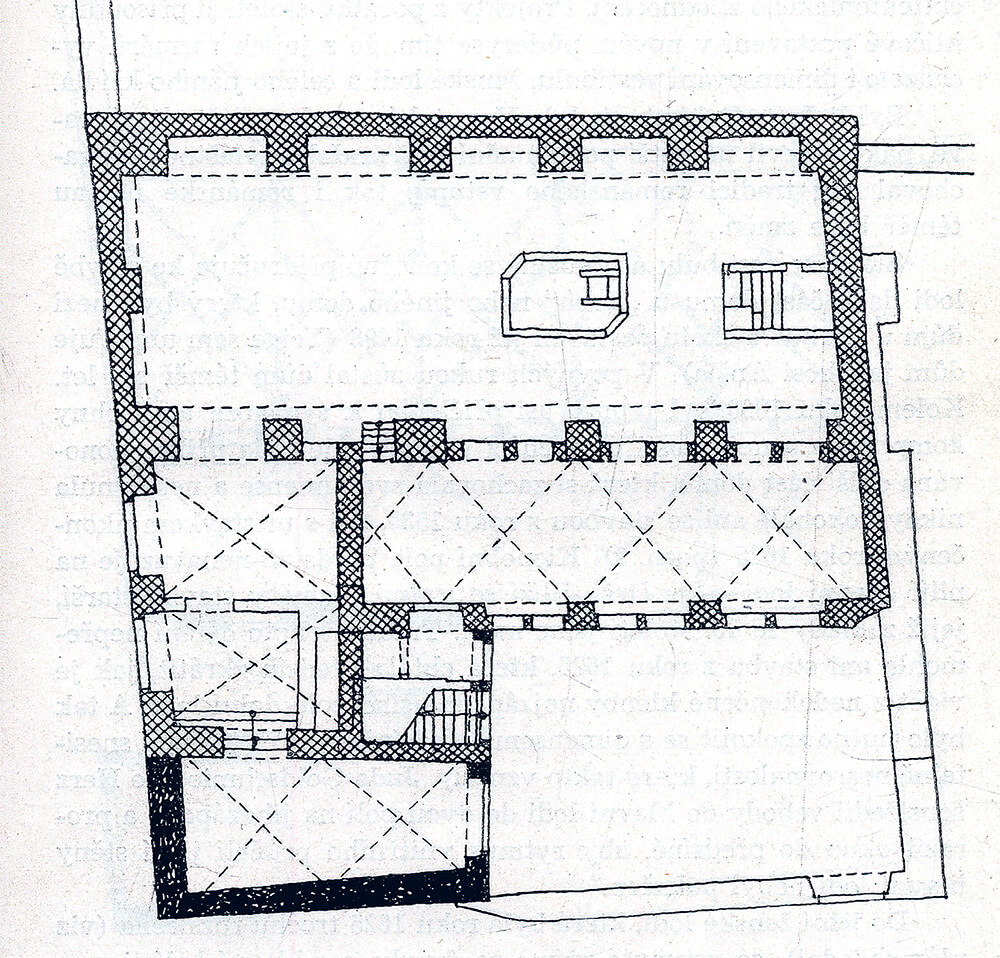

Jewish Museum in PragueThe high single-nave area of the Pinkas Synagogue has a late-Gothic reticulated vault with painted motifs. The original architectural character was made complete by the rich stone decoration of the Holy Ark and bimah (podium). The building also includes a number of early Renaissance features, the most advanced of which adorn the entrance portal to the main nave.

The synagogue remained in the hands of the Horowitz family throughout the 16th century. A late-Renaissance annex, designed by the architect Judah Tsoref (d. 1625), was added to the building between 1607 and 1625. The annex included a women’s section on the south side of the main nave and a women’s gallery above, together with a spacious vestibule and an arched entrance hall. The reconstruction project also involved altering the synagogue facade facing onto Pinkas Street and the courtyard facades, which have late-Renaissance paired windows and a portal.

The narrowing west part of Široká Street, where the Valentine Gate stood until the end of the 18th century – for centuries the main entrance to the Prague ghetto. Zikmund Reach, ca. 1905.

City of Prague MuseumIn the last third of the 19th century, the west part of Široká Street was called Pinkas Street. On the right you can see the facades of old buildings around the Pinkas Synagogue; in the background, Pinkas Street turns off to the right, ca. 1905.

Prague City Archives, Photograph Collection, Call No. I 11960. František Fink Ad kolorovaná kresba: Jewish Museum in PragueThe Pinkas Synagogue’s low elevation and the insufficient flood protection of the entire area were the main causes of repeated flooding. After flood damage in 1860, the synagogue interior underwent radical modernization. The floor level of the main hall and vestibule was raised by 1.4 metres. At the same time, the bimah was covered over with back-fill material, the Baroque decoration of the holy ark was removed, and the Renaissance portal was walled up. The old seats were replaced by benches, and all the fixtures were modernized in a Neo-Romanesque style.

The Moses Reach Junk Shop, selling old iron, dishes, clocks and bird cages, used to be in the west part of Široká Street near the Pinkas Synagogue. Jindřich Eckert Studio, ca. 1905.

Jewish Museum in PragueSome time later, the area around the Pinkas Synagogue was changed beyond recognition by the redevelopment of the Jewish Town. All the old buildings surrounding the synagogue were demolished between 1907 and 1910. The level of the surrounding terrain was considerably raised, as a result of which the synagogue sank deep below the surface of Široká Street. In 1925, the Construction Commission and representatives of the Heritage Office recommended removing the backfill, undertaking an archaeological survey and preparing a new regulatory solution for the entire area, but these measures were not carried out.

The final phase of the redevelopment of Prague’s Jewish and Old towns: demolition of a block of houses with a view of the Old Jewish Cemetery, Klausen Synagogue, Pinkas Synagogues and the Museum of Decorative Arts. Jan Kříženecký, 1909.

Prague City Archives, Photograph Collection, Call No. XI 1339

Pinkas Synagogue after demolition of the surrounding buildings and landscaping. This photo shows the early 17th-century annex of the synagogue and its facades, which had previously been concealed by the surrounding buildings. Karel Dvořák, ca. 1910.

Jewish Museum in Prague